-

THE BOOK IS HERE.

ALSO, THE PODCAST, AN ARTICLE AND A SLIDESHOW.

Welcome to the website home of the project titled “Civil War Survivor: Incredible True Story of a Union Private.” This is the introduction to a slide show, a podcast, a future magazine article and a future Amazon book.

The four-minute slide show is all words and music.

The podcast is an abbreviated audio book along with Civil War-era music. You can find it on Spotify, Podbean YouTube, Apple and Pocket Casts with a search for “Civil War Survivor.” It is slightly out of order. You’ll find Episode 2 later in the list.

THE BOOK

The Amazon ebook and paperback include edited portions of 181 letters sent by Edgar to his wife Catherine along with my commentary based on Civil War research involving over 170 books, interviews and sources. Also included are original photos, maps and illustrations. The paperback is available for $24.99 on Amazon. The ebook is available for $9.99 or for free with Amazon Kindle Unlimited. Here is the Amazon link: https://tinyurl.com/3tcjyhav

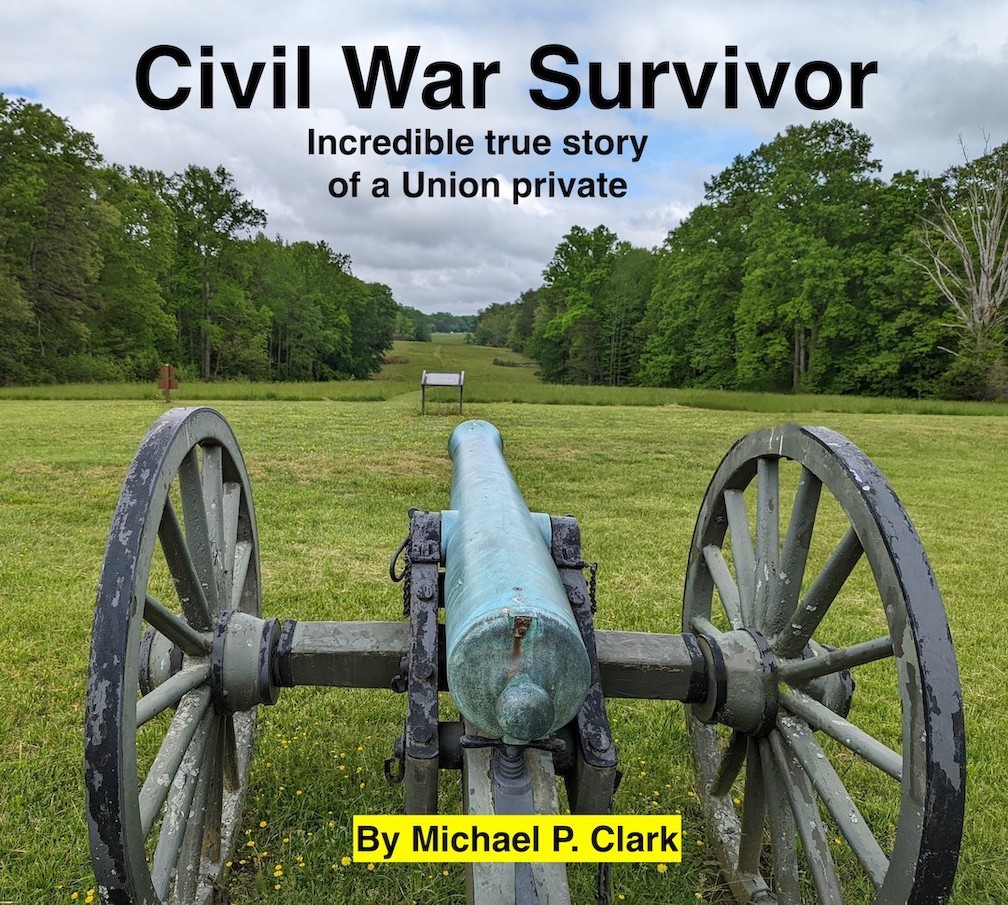

A note on the cover photo. This is Hazel Grove from the Chancellorsville Battle site. Note the elevation — a perfect platform for artillery. Gen. Daniel Sickles occupied this site and considered it a perfect spot to wage a counter-attack against the separated Confederate forces. Instead, Gen. Joe Hooker ordered Sickles to abandon the spot. It was immediately taken by Confederate Gen. Porter Alexander, who used it to send barrages at the Union forces, including the Chancellor House far in the distance. You also can see the dense woods where Union forces fired on each other at night.

THE PROJECT

Edgar W. Clark survived the terrible devastation of the war that saved the Union and ended slavery. He participated in a stunning series of events during the Civil War — 40 days of combat and 13 battles. But that’s not all. He survived months of hospitalization, he narrowly avoided capture and he survived being shot.

But the story of Edgar W. Clark is much more than a series of battles. Through the lens of 181 letters sent home to his wife, Catherine, Edgar described what it was like to have left a wife and two young daughters to help save his nation and in the process end slavery in the USA. At one point, Catherine had to move back with her family. Indirectly, this is the story of the sacrifices that a young family made so the nation would remain whole and end slavery. Make no mistake, Edgar knew why he was fighting.

So this project includes both hard and soft aspects of the Civil War: the family life of a soldier as well as the larger military, political and social issues swirling through the nation at the time.

THE STORY AND THE AUTHOR

I am Michael P. Clark, the great-great-grandson of Edgar W. Clark. I am retired after about 50 years in print journalism, the last 15 years spent as Editorial Page Editor of The Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville. My father gave me possession of Edgar’s letters decades ago, which I transcribed and edited. But I could never justify a book until I had fully researched what was happening during the battles and in the nation at large. I found that time after retirement in December of 2020. During my research, I learned some fascinating storiess about the Civil War, which are includedd in the book and podcast.

In 1861, when Governor Austin Blair asked for volunteers to help save the Union and put down the rebellion, Michiganders responded at once. Edgar joined the 3rd Michigan Infantry Regiment one year later on Aug. 11, 1862, leaving a wife and two daughters, 1 and 3, at home.

In his first big battle, he supported artillery at Fredericksburg in December of 1862. Though a cannonball bounded over his head, he luckily wasn’t asked to charge up Marye’s Heights, a killing field that was a precursor to Pickett’s Charge.

That winter, he was laid up for months in Union hospitals with diarrhea that would only be cured with opium.

In May of 1863 at Chancellorsville, at the crucial location of Hazel Grove, he fought in a crazy night attack in which Union troops fired on each other in the woods. The photo shows the elevation there, a perfect artillery platform that Union Gen. Joe Hooker abandoned to the rebels.

A month later at Gettysburg, he was sent to the front, the Peach Orchard, where Union artillery waged a ferocious duel with Confederate artillery. This was a key to the battle due to its elevation. Edgar again was lucky that his unit did not suffer the same level of casualties as other Union units on the second day, the bloodiest day at Gettysburg.

One month later, the 3rd Michigan was sent to guard draft offices in New York City and Troy, N.Y. It was a break and Edgar wrote that some soldiers found girlfriends and even a few brides there.

A year later, in the summer of 1864, U.S. Grant took over and the battles were almost continuous. In the Wilderness, Edgar survived more intense fighting. And at Spotsylvania, he was in the 4 a.m. attack that was so ferocious that a portion of the Mule Shoe salient was called the Bloody Angle. The photo of the current site of the Bloody Angle is deceptively idyllic. As described on the plaque by the National Park Service, fighting at the Mule Shoe Salient focused on Confederate earthworks to the right front, the Bloody Angle. Whoever controlled this slight knoll controlled the salient, an area jutting out of the Confederate lines that was vulnerable to attack from several sides. The battle, which began at 4 a.m., involved the 3rd and 5th Michigan Infantry Regiments, among others. Union soldiers took cover in the ravine in front. Over 22 hours, attacks pulsed back and forth with bodies piling up into ramparts of the dead.

Finally, at Petersburg in June of 1864, Edgar was sent to assault Confederate entrenchments on the second day of battle and was shot in the left knee.

His leg was amputated at a field hospital and then he was sent to a series of Union hospitals in Washington, D.C. There he survived gangrene and returned home, a one-legged man.

Edgar died in 1902 at the age of 68. That sounds pretty pedestrian except that in the 1860s when Edgar fought in the Civil War, the average American lived only to the 40s.

Edgar W. Clark returned home about 2 ½ years after he left. Before he left, he and wife Catherine had two daughters. After he returned, they had two sons. One of them, Amos, a Lansing firefighter, is my great-grandfather.

Mt. Hope Cemetery in Lansing, Mich., Edgar’s hometown, holds his grave and those of other Lansing men who followed President Abraham Lincoln, another humble Midwesterner.

There are many letters and memoirs from Civil War soldiers but I contend that very few describe the eyewitness action of so many historic battles as Edgar W. Clark. And it would be remiss to ignore what his wife endured at home with two toddlers to care for.

THE SLIDE SHOW

While watching the slides, pay close attention to the elevation of the battle sites. Imagine yourself trying to storm up one of those hills. How foolish it seems to us that generals of either the North or South would order their troops to scale such heights.

Also, near the end of the slide show, examine how crowded Harewood Hospital is in Washington, D.C. Union doctors eventually learned that providing lots of space and ventilation lessened the chance of infection.

THE PODCAST (Podbean, Spotify, YouTube, Apple and Pocket Casts)

The free podcast is like an audio book, a shortened version of the book complemented by Civil War-era music. Most of the episodes end with appropriate Civil War music. My three favorite pieces of music are “Weeping Sad and Lonely” after the Gettysburg episode 5, “Battle Hymn of the Republic” after Episode 8 and “The Cruel War” after Episode 10. There are eight episodes involving the letters of Edgar W. Clark. There will be at least five more episodes related to Civil War subjects that I discovered in my research. I am indebted to the musicians who contributed to this project. See the acknowledgments below. Each episode is about 30 minutes long. In addition to the Edgar Clark letters, I have included interviews with outstanding authors, such as an expert on Henry Clay, Mary Todd Lincoln and the co-author of a book on women who dressed as men to fight in combat in the war. There are 13 episodes and I am working on two more for 2025.

THE MAGAZINE ARTICLE

A story was published in the 2024 summer edition of Chronicle magazine by The Historical Society of Michigan. It is about 2,500 words, with photos and excerpts from the letters. The article hits the highlights of the project. For copies, email: [email protected].

CONTACT

For more information, send me an email: [email protected].

CREDITS: PHOTOS, GRAPHICS

Gettysburg Photos: Darryl Wheeler.

Mt. Hope Cemetery Photos: Matthew VanAcker.

Maps, Illustrations: Jonathan James.

Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, Hospitals: Library of Congress, Alamy.

Hazel Grove, Bloody Angle: Michael P. Clark.

Petersburg: Ray Richardson.

Blair statue at the Michigan State Capitol: Michigan State Capitol Commission.

CREDITS: MUSIC

The Homespun Ceilidh (“Kay-lee”) Band: “Amazing Grace,” “Be Thou My Vision,” “Hard Times,” “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp,” “Bonnie Blue Flag,” “Battle Cry of Freedom,” and “Nearer My God to Thee.”

The 92nd Regimental String Band: “Weeping, Sad and Lonely.”

The Michigan State University School of Music: “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Hannah Fridenmaker: “The Cruel War.”